Why Metrics Fail in a Complex World

How our obsession with metrics gets us into trouble

Zappos, the popular and quirky online retail company, started the adoption of Holacracy, an organisational operating system, in 2013 and went full-commitment in 2015.

Radical! Holacracy involves a complete migration away from hierarchies and bureaucracy to a meritocratic system based on evolving roles and distributed responsibility. In the process, 150 departmental units at Zappos evolved into 500 circles of responsibility. Imagine that!

However, sadly, things didn’t go well. By 2015, nearly one in five employees had decided to leave the company. The loss of experienced talent and the dip in morale had a deep impact on the company.

What went wrong? It turns out that, in order to try to manage such a huge change effectively, the company decided to track all their efforts using two key metrics:

the number of active roles,

the clarity of their definitions.

Unwittingly, this put all the focus on the roles themselves, encouraged rigidly defined roles and placed the organisation under constant pressure to create more and more roles to cover organisational needs. This led to confusion, frustration, and a feeling of constant restructuring.

While the intention of adopting Holacracy was to empower employees, the focus on the roles almost sank the initiative. The emphasis on the structure overshadowed the actual effectiveness of collaboration and communication.

Shocking if you think about it, but sadly, this is not an isolated incident. It illustrates a tendency I’ve noticed more often: an almost religious faith in metrics, and a blind over-reliance on them as if they were the only way to manage complex systems.

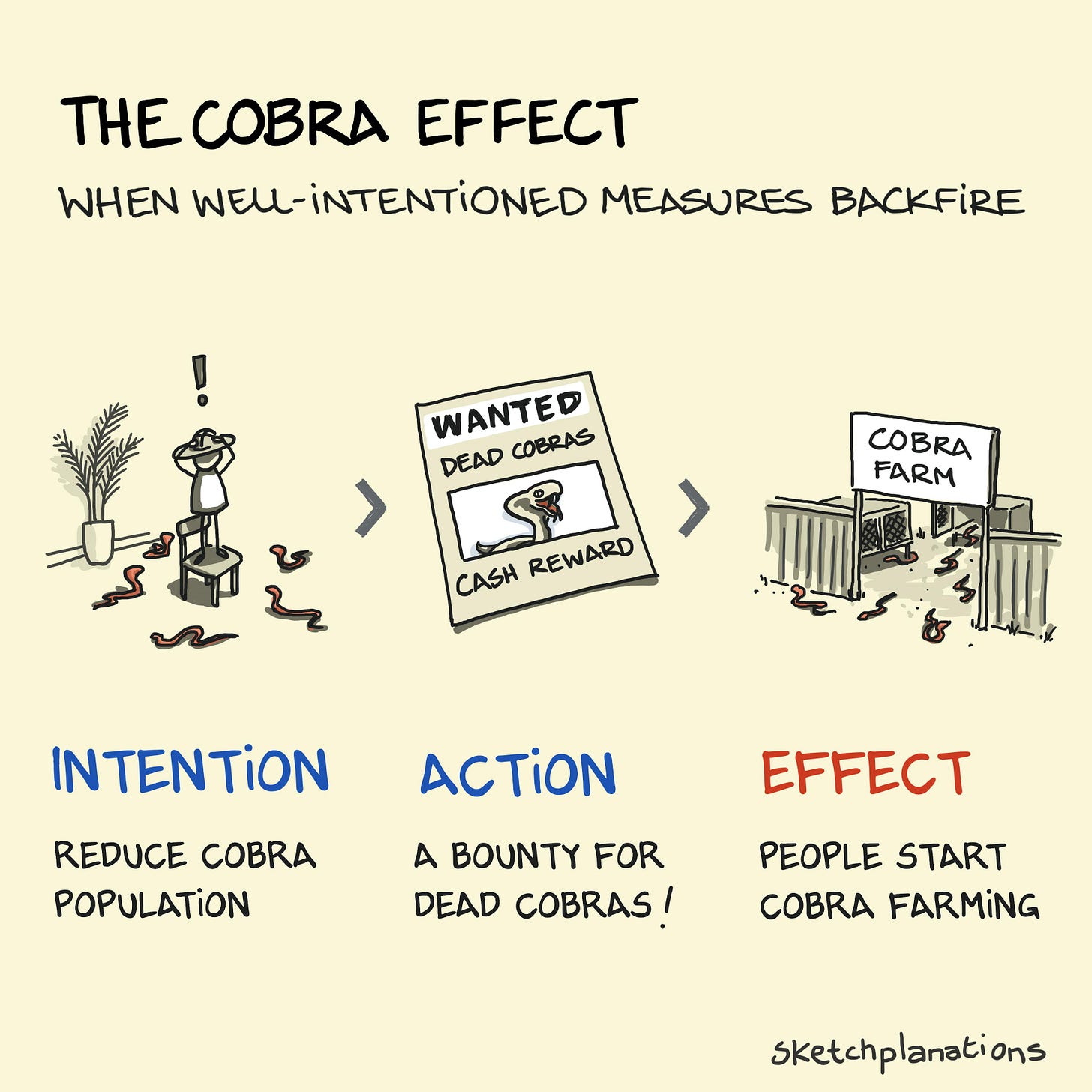

This over-reliance often leads to unintended, detrimental consequences. And the examples are legion, situations where focusing on metrics completely derails the good intentions of an initiative:

Facebook focusing on engagement as a metric, leading to the spread of misinformation to create outrage, and culminating in the terrible Rohingya massacres in Burma.

Boeing focusing on maximising stock value, resulting in catastrophic quality issues with airplanes literally falling out of the sky.

The teaching to the test phenomenon in education, that saw schools put all their focus on writing and maths exams at the expense of creativity and problem-solving skills across an entire generation.

The Average Handle Time in call centers, which literally ended up putting quantity over quality, to the detriment of customers calling for help.

So yes, metrics. How did we get here? Where did we go wrong?

Complexity

Enter Complexity, a world where causality, the reliable relation between cause and effect, simply does not exist. According to Wikipedia,

Complexity characterizes the behaviour of a system or model whose components interact in multiple ways and follow local rules, leading to non-linearity, randomness, collective dynamics, hierarchy, and emergence.

The important part of this definition is the last bit: “leading to non-linearity, randomness, collective dynamics, hierarchy, and emergence“. This literally means that the reliable and linear relationship between action and effect simply ceases to exist. And with it, our ability to predict events, which is the very reason we use metrics. It is what Cal Newport calls the “black hole of metrics”.

All the examples mentioned in the introduction are complex systems, and - let me rub this in - by definition, a complex system cannot be measured reliably. It is precisely the characteristic of being hard to measure that makes a system complex.

Complexity is the challenge of our age.

We have lived for a very very long time in a world where we could ignore complexity and just focus on the complicated. A world where the relationship between cause and effect is reliable and where, with the right analysis and expertise, anything can be modelled and therefore predicted.

This is precisely the kind of world where metrics shine. Witness 500 years of innovation since the dawn of the Enlightenment and the huge expansion of science that followed, and culminating in the Industrial Revolution.

It has formed our societies and our way of thinking to such an extent that we take it for granted. We instinctively grab a ruler, a calculator, a planning sheet, a process, a framework whenever we are faced with a challenge.

Scientific Management is nothing more than an iteration of this approach, treating an organisation like a machine (a complicated system), with people as resources (neatly avoiding complexity), and managed by mechanics (managers).

Metrics are so ingrained in our way of thinking that organisations live convinced about their ability to measure anything. Agile Maturity Metrics, DORA metrics, Kanban metrics, Lead & Cyle Time, KPIs, OKRs! We have metrics for everything. Metrics galore to satisfy our greedy data addiction.

Dealing with Complexity

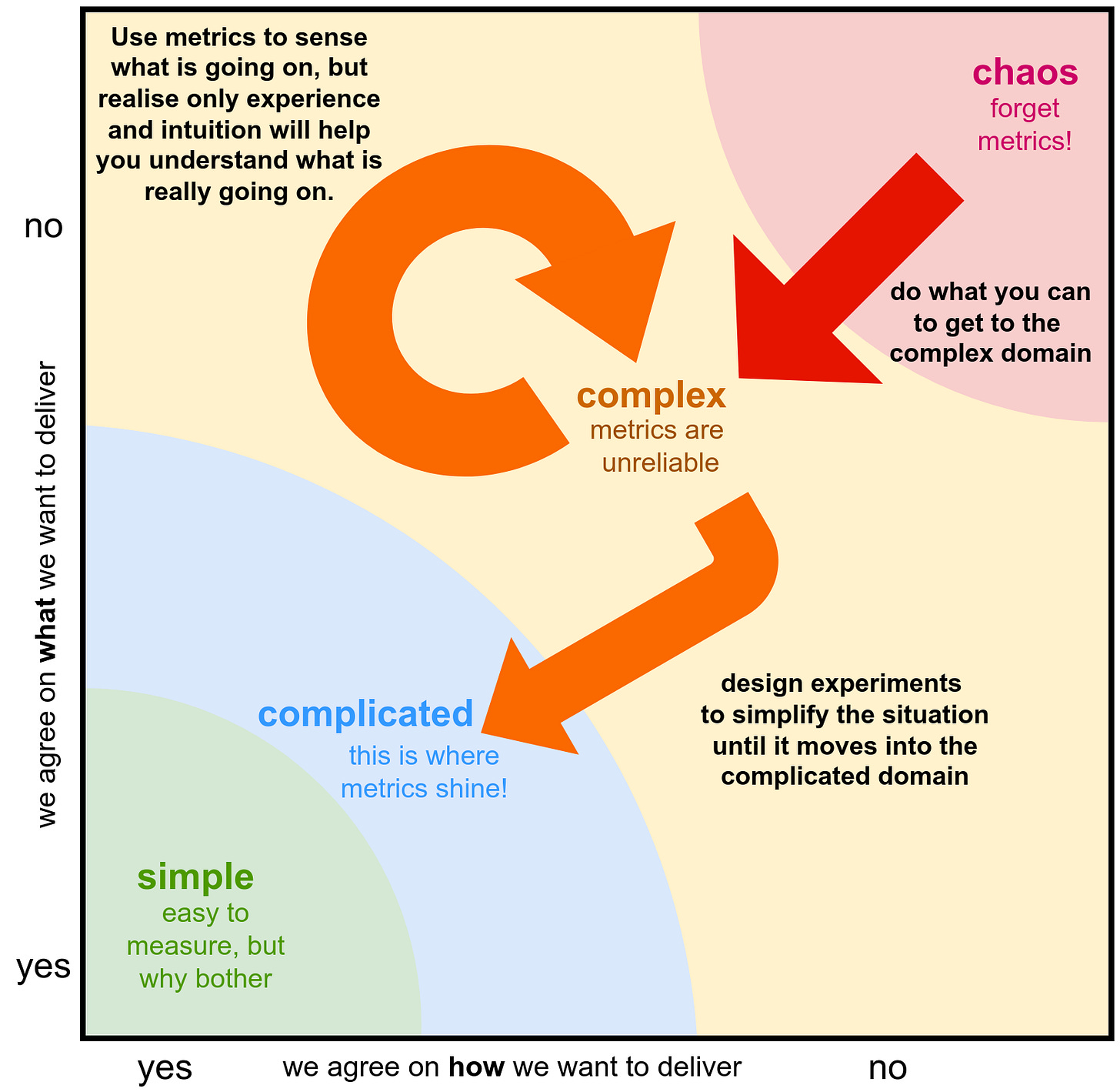

When faced with complexity, our instinctive and historically effective approach, deeply rooted in empiricism, has been to apply the Scientific Method. This method roughly involves reducing the complexity of a system by creating controlled conditions, thereby reducing the number of variables until the problem moves to the complicated domain, making reliable and reproducible causality possible. This is what creating experiments is all about, and it is the reason why perhaps the hardest thing scientists do is design experiments.

Indeed, it is from this very approach that our addiction to metrics stems, as it thrives on quantifiable, reproducible results. In the diagram below, you can see how that works in more detail, in the context of complexity.

This is an effective approach, but ultimately it is an approach that relies on causality, which is a property of the complicated domain. And herein lies its limitation. It means metrics only work in the experimental setting, within those controlled conditions. And since meticulous and reproducible experimentation is required for each step, it means that the approach is a slow, slow process.

In our volatile, uncertain and fast-paced world, such methodical slowness becomes a critical liability. Things are happening now, and we simply do not have the time.

Accepting the limits of metrics in complex systems is essential to start dealing with complexity. This is hard. It means accepting that we need to discard many of the tools that we currently rely on. Yet, this challenge presents an immense opportunity. By breaking free from the constraints of a Tayloristic world that has perhaps been pushed to its extreme, we can truly unleash our human potential in the pursuit of new ways to deal with complexity.

The truth is that aspects of agility such as the focus on value, working with small teams and involvement of stakeholders are all remedies for our addiction to metrics. They point the way towards a new way of perceiving what is going on in complex environments.

Agile has laid the groundwork, providing an effective foundation for a learning organisation. It has also allowed us to take the first steps in developing new more intuitive and context-driven ways to deal with complexity, such as systems thinking, intuition, retrospectives, design thinking and patten recognition.

Conclusion

So what then, are metrics completely useless?

No, absolutely not! They are an essential way of sensing a situation. However, the key is to understand their limitations and use them accordingly. In a complex system, metrics are a supplement to our intellect. They only give us a glimpse of particular parameters in a vast, interconnected web. It is up to us to discover innovative ways to interpret and make sense of the information metrics provide us.

It’s a bit like when you drive a car. You have your speed gauge and you know what speed you need to drive on this particular piece of road. You can see your oil pressure and the amount of fuel you have. Nowadays, you even have navigation gadgets to find your way. But even with all these gauges and aids, nobody would think about painting over their windshields!

Instead, driving is mainly about looking out to what traffic is doing around you, because that is the only effective way of coping with that level of complexity.

Just like a driver, we need to accept that the raw information from our metrics needs careful interpretation within our unique context. And this need for interpretation means two things:

we need knowledge and experience to be able to make sense of the data,

interpretation introduces uncertainty and a degree of subjectivity, as there's no single, universally quantifiable 'right' answer.

Our focus therefore should shift from simply collecting more data to developing the necessary skills and tools to interpret all these tidbits of information.

We need to start accepting our innate abilities to deal with complexity, much like how we instinctively rely on our ability to track and coordinate the movements of all the traffic around us to drive safely.

The smell of the place is a good way to describe this new perception. It is that gut-level feeling you immediately get about how things really are in an organisation. It is something really hard to explain, and for many it is hard to rely on. Intuition is hard to trust.

Employee happiness is another example. But not as something you measure with an assessment but as that feeling you instinctively pick up when you interact with individuals and teams. I’ve written about my own experience using our innate ability to sense happiness as a way to measure team Effectiveness.

And this is precisely the awkwardness of this approach, that these are things you perceive and ‘measure’ without quantifying them. Either because it is right-out impossible due to the high level of complexity or because the effort to measure it would be prohibitive. By the time you actually measure it, the moment is gone.

The bottom line is that in a complex system, we need to find new ways of making sense of reality that move beyond our over-reliance on metrics.

It is a brave new world in which only those able to embrace a new intuitive and awkward way of sensing what is going on will thrive and prosper.

The focus on value is a good example. I had a team once where we considered how to measure values. After a long, serious discussion, unable to find an effective way to measure it, we ended up giving up on the idea of quantifying value. However, that conversation stayed with us. And it turned out that simply by having had that conversation, it created an acute awareness of the idea in the team. This awareness popped up everywhere. If during a refinement, the conversation got away from us, someone would just say ‘business value’ to get us back on track. Prioritisation questions were easier to resolve - just remember ‘business value’. And so on.

An idea can still be powerful, even if you cannot measure it.

Another nice read Erik! Well done indeed.

One small detail I'd maybe change is the 'get rid of the windscreen' - it left me a bit confused at first. Instead you could say something along the lines of 'replace their glass windscreens with a metal one (for safety? :D)

Just my €0,02